Source: Hindustan Times dated 08.11.2019

-- Maja Daruwala (Chief Editor of the India Justice Report 2019)

The report uses government data from 2012 to 2019. Tata Institute of Social Sciences’ field action project, Prayas, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Common Cause, Centre for Social Justice, DAKSH, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, and data partners How India Lives have worked on the report, led by the Tata Trusts.

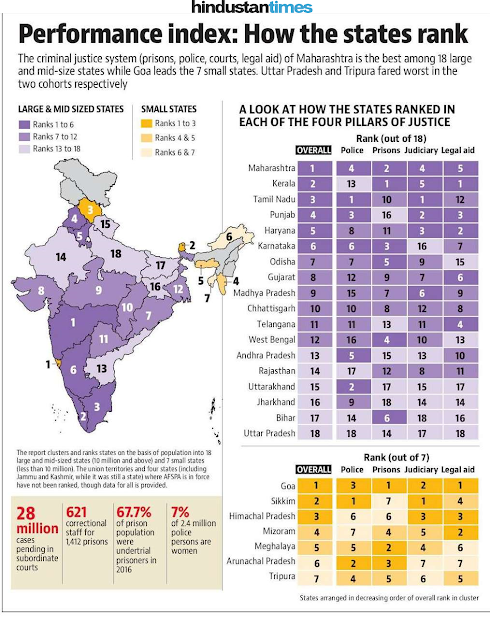

In a first, Indian states have been ranked using government data on police, prisons, judiciary and legal aid, across themes like budget, diversity, human resources and infrastructure. States’ efforts to improve have also been mapped.

-- Maja Daruwala (Chief Editor of the India Justice Report 2019)

The report uses government data from 2012 to 2019. Tata Institute of Social Sciences’ field action project, Prayas, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Common Cause, Centre for Social Justice, DAKSH, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, and data partners How India Lives have worked on the report, led by the Tata Trusts.

What happens when you measure states against the standards that they have set for themselves in delivering social justice to citizens? You get an index that can reveal a lot about not just quality of life of the citizenry, but also about the state’s intention to improve the lives of the people. The India Justice Report (2019) does just that: we put together quantitative assessments of the four pillars of the justice system — namely, police, judiciary, prisons, and legal aid — using only government data from the past seven years, sourced from the National Crime Records Bureau, Bureau of Police Research and Development, the National Judicial Data Grid, and the National Legal Services Authority, among others.

Within each pillar, we examined six main themes — budgets, infrastructure, human resources, workload, diversity, and five-year trends — to measures states, not just against each other, but also against the standards they have set for themselves. Thus, this report for the first time consolidates data, otherwise disparate and siloed, to present a complete picture of the state of social justice in India.

Collectively, the data paints a grim picture. It highlights that each individual sub-system is starved for budgets, staff and infrastructure; no state is fully compliant with the standards it has set for itself, be they quotas for women or for scheduled castes, scheduled tribes and other backward classes. At the same time, the report also shows how the ranking of certain states is pulled down because of their rank in one pillar. For instance, Kerala, despite being a top-ranking state, is pulled down because of its rank in the police. Here are some highlights of the report that could go some way in explaining why things are the way they are.

A host of vacancies

Human resource is the backbone on which the pillars of the justice system rest. The report revealed huge vacancies across all four pillars and in each state. On average, the police have a vacancy of 23% (2017), and the judiciary between 20%-40% across the high courts and lower judiciary.

A closer inspection brings forth alarming figures: as of January 2017, the Uttar Pradesh police was functioning with a 63% vacancy among officers, while the constabulary was at a 53% vacancy against its sanctioned strength. Across a five-year period (2012-16 and 2013-2017) Gujarat had consistently reduced its vacancies across all pillar posts and positions, while Jharkhand had seen an increase in its vacancies over the same time period.

The result of staff shortages is an increased workload on functionaries. This is what it looks like: one subordinate court judge for over 50,000 people in 27 states and union territories; more than 1,900 persons served by a single police person in Andhra Pradesh; one sanctioned correctional officer in Uttar Pradesh’s prisons looking after an average of more than 95,000 prisoners. Needless to say, this workload stress is as bad for the functionary as it is for the dispensation of justice.

Missing people

Diversity reinforces the notion of equity and equality, promotes inclusiveness, and most importantly raises public trust in the system. The unevenness of collection practices and data gaps, however, did not permit a fair comparison and assessment of various kinds of diversity across the four pillars. Data on caste representation, for instance, was only available for police; the profile of gender was discernable across all.

Women are poorly represented across the justice system. Nationally, they account for 7% of the police (as of January ’17), 10% of prison staff (as of December 2016) and about 26.5% of all judges in the high courts and subordinate courts (2017-18). Nowhere except in the lower judiciary in some states had the 33% reservation figure been reached. The data also affirms the existence of a glass ceiling where most women tend to be clustered amongst the lower ranks.

Nationally, a majority of states are unable to meet their declared caste quotas. In all, 16 states and UTs were able to meet or exceed the sanctioned figure of caste and class reservation which they set for themselves. Karnataka was the only state to have very nearly filled officer-level reservations in all caste categories (as of January 2017).

Budgets

Everywhere, increases in budgets for the justice system are not keeping pace with overall increase in state budgets. For example, while most states have been showing increasing annual spending on the judiciary, this is less than the increase in the overall budget. For instance, Rajasthan saw a difference in spending of 12 percentage points, while its total budget increased by 20%, its judiciary budget grew by only 8%. This is indicative of the priority accorded to each sub-system. Punjab was the only large state whose police, prison and judiciary expenditures were able to increase at a pace higher than the increase in overall state expenditure (for the Financial Years 2012-2016).

The report also compares capacity and accessibility to sub-systems in rural and urban areas in terms of police stations and legal services clinics. Rural India is at a disadvantage. Urban police stations in as many as 14 of our 18 large states serve smaller areas and smaller populations. The average area covered per rural police station, however, in 28 states and UTs exceeds 150 sq. km, a benchmark given in 1981 by the National Police Commission. What this means is that there are not enough police stations for rural India, and access to justice is harder — and farther — to reach.

It’s the same issue with legal services clinics. In 2017, a total of 14,161 clinics existed across around nearly 600,000 villages. The 2011 Regulations require clinics to be set up in all villages or cluster of villages, subject to resources. There are only 11 states and UTs where a legal service clinic covers, on average, less than 10 villages. In Uttar Pradesh, this figure is as high as 1 for every 1,603 villages.

Pending woes

On the one hand is access to police stations and legal help, on the other, is judicial pendency. Nationally, at the subordinate court level, on average a case remains pending for five years or more. The range, of course, varies: as of August 2018, cases in Gujarat’s subordinate courts remained pending for up to 9.5 years on average, while in Rajasthan’s subordinate courts the average wait was 3.7 years.

In general, the number of cases pending is on the rise. As of 2016-17, only six states and UTs i.e. Gujarat, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Tripura, Odisha, Lakshadweep, Tamil Nadu, and Manipur managed to clear as many court cases as were filed. As on August 2018, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Gujarat, Meghalaya and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, had nearly 1 in 4 cases pending for more than 5 years.

Road to reform

The disaggregation of official data in the report is useful in pin-pointing the inflexion points that, if tackled, can set up a chain reaction towards reform. Concerning itself purely with the structural anatomy of the justice system, the report does not make comments on perceptions of safety, performance or accountability. However, much about the quality of justice can be discerned from shortfalls in its structural capacity. That is if we expect to have enough well-staffed and well-equipped hospitals and clinics, why shouldn’t we expect the same of our justice system?

This report suggests nudges which, if undertaken, will assist in stirring momentum for reform, improve a state’s future ranking and, more importantly, improve the delivery of justice to all. States like Bihar which, despite scoring poorly across most pillars, scored well in prisons by reducing vacancies and improving budgetary allocation. Good practices such as these can be applied to other pillars to improve performance in future rankings.

Though ranked 15th overall, Uttarakhand comes second in the police pillar buoyed by low vacancies at the officer and constable level (as of January 2017), a decline in officer-level vacancies over five years (2012-2016) as well as an increase in women officers over the same period.

The delivery of justice is an essential service. The Constitutional promises of “equality before the law” (Article 14) or the universal duty of all governments to ensure “the protection of life and personal liberty” (Article 21), however, will remain unfulfilled so long as justice remains a luxury accessible only to the privileged and powerful.

No comments:

Post a Comment